How a Fire Built Singapore

a pivotal point in HDB's success

Gradually we should be able to re-educate the people into more considerable and cultivated living. And when they move out from the squatter huts into modern homes, they must leave their own inconsiderate ways behind.

- Lee Kuan Yew1

In May 1961 a huge, unprecedented fire ripped through the wooden houses in the urban kampong of Bukit Ho Swee. The inferno destroyed over 2000 dwellings, left over 15,000 people homeless, and claimed four lives.

But the fire isn’t only historically significant for the destruction it caused, but for being the pivotal moment that changed Singapore’s housing situation and policy.

Kampongs, semi-autonomous communities commonly home to low-income Chinese families, were freely built, unauthorised wooden houses, and they once dominated Singapore. But the Bukit Ho Swee fire turned Singapore into a city now dominated by high-rise blocks of planned public housing.

Today, HDB flats are one of the most recognised aspects of Singaporean living. They are home to 80% of Singapore's resident population, of which about 90% own their home2. But the journey here can be traced back to the Bukit Ho Swee fire of 1961.

Want to watch this post instead?

Origins of the urban kampong and Bukit Ho Swee

After the Second World War, Singapore experienced an influx of immigrants, many of whom settled in urban kampongs. And by the early 1960s, these Kampongs housed a quarter of Singapore's urban population. The kampongs largely functioned as autonomous areas, with many residents taking up jobs in an informal economy. This autonomy in the kampongs led to the colonial government perceiving the kampongs as socially undesirable areas, which they had little authority over. So, logically, the government’s preferences for Kampongs were they wanted them to be cleared and replaced with more traditional, yet also more modern, public housing.

The British colonial government in Singapore, through the Singapore Improvement Trust, was pushing hard for public housing development to support Singapore's industrialization process. Kampongs were often cleared to free up land for the construction of public housing units. Yet, the high rents and small size of the flats meant that they were not popular with residents of urban kampongs. Justifiably, many residents chose to remain in kampongs.

This situation of managing the reality of lower-class Singaporeans, with the government's aspirations for a more modern, industrialised society, would soon be thrust to the forefront in the aftermath of the Bukit Ho Swee fire of 1961.

The Inferno and Government Response

Kampongs, made out of wooden structures, made their fire risk more of a case of ‘when’ not ‘if’. Improperly disposed rubbish, burning joss sticks in religious rituals and the use of firewood for cooking all meant that kampongs were constantly only an errant spark away from going up in flames.

Not just a fire risk, the fire brigade solution wasn’t much better. For Singapore’s entire population of over 1.4 million people in 1957, they only had 25 officers, 37 subordinate officers and 370 other firefighters.

It was Thursday, May 25, 1961. Coincidentally, the same day JFK announced America’s goal of putting a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. But for Singapore, it was the Hari Raya Haji public holiday, the biggest holiday celebrated in Islam. The Singaporean fire brigade was already behind the eight ball leading up to the fire, but to compound this on the day of the fire, many of the firefighters were Malay Muslims who had taken leave to celebrate the festival. Making an already depleted fire brigade even more susceptible.

At 3:30 pm on 25 May 1961, a small fire started in the neighbouring Kampong Tiong Bahru. The wind conditions and flammable nature of the kampongs meant that the fire spread quickly.

The scale of the fire was immense, with an area of approximately 100 acres being guttered. Over 2000 dwellings were destroyed, more than 15,000 people were left homeless, and four people lost their lives.

The Bukit Ho Swee fire peaked around 8 pm, with 22 fire engines having been deployed. The fire was eventually extinguished at around 10 pm. But not before the fire had left a massive trail of destruction in its wake.

After the fire, a national state of emergency was declared and local schools became temporary relief centres. Given that the residents escaped with few of their belongings, the fire also significantly damaged the local economy. But as the government stepped in, this is when the wheels of change really started to turn…

How the fire propelled HDBs

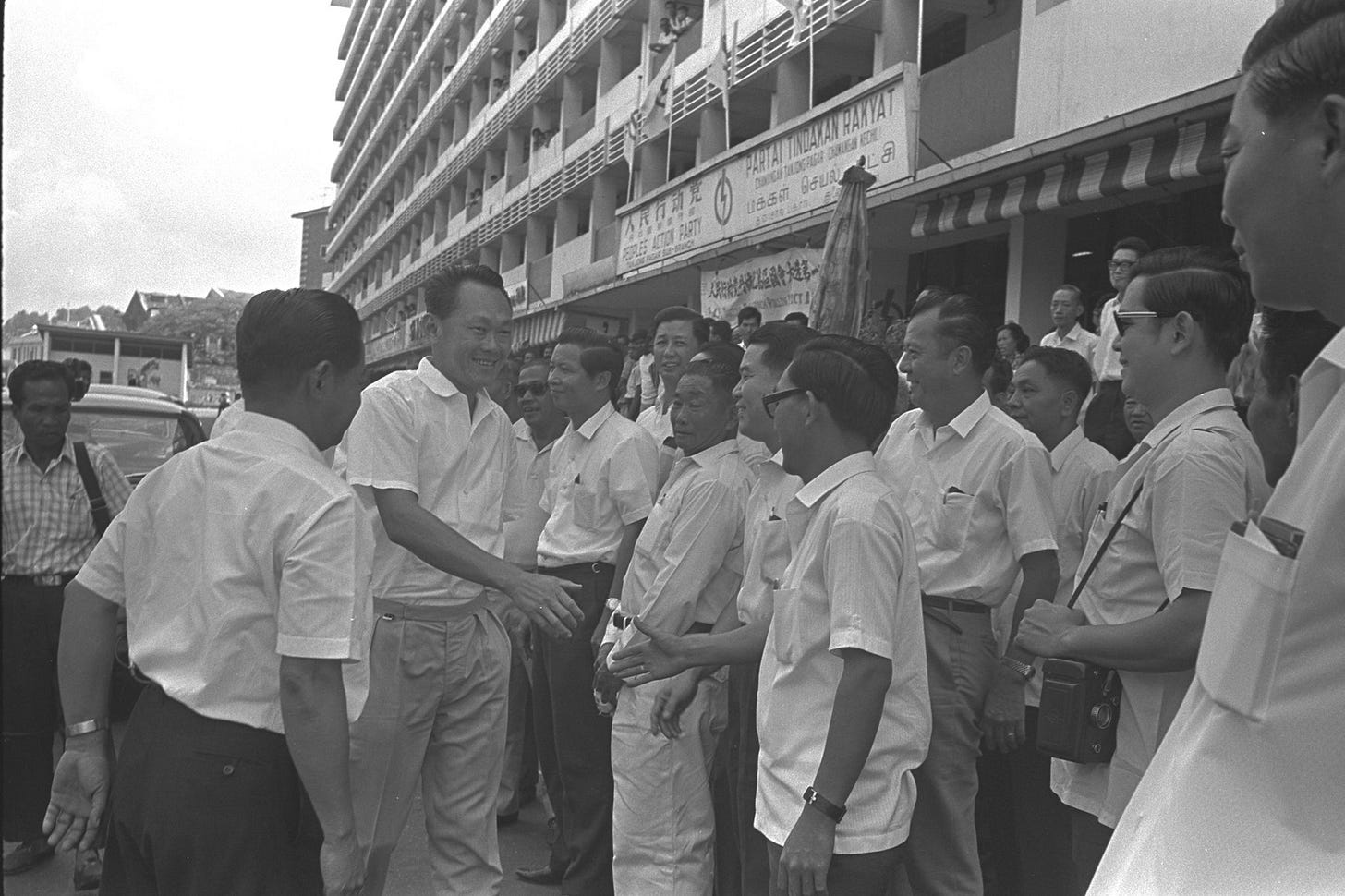

The response to the fire by The People's Action Party was swift. The PAP, sensing an opportune moment to implement their public housing development plans, leveraged the Bukit Ho Swee fire and the subsequent emergency construction of public housing for their political purposes. They wanted the newly completed public housing flats to showcase the progress of Singapore, demonstrating to both locals and the international community how Singapore had transformed itself from dangerous settlements into a modern metropolis that could provide immaculate and safe housing for its people.

For the People’s Action Party, the fire enabled the government to remodel the kampong dwellers into disciplined citizens, in planned housing, who contributed regular rental payments as workers in the new industrial economy. In other words, it tamed the ambivalent zones of the kampongs and transitioned residents to the new Singapore, and in the process, to the government. The transformation effectively became a metaphor for the progress of Singapore under the PAP.

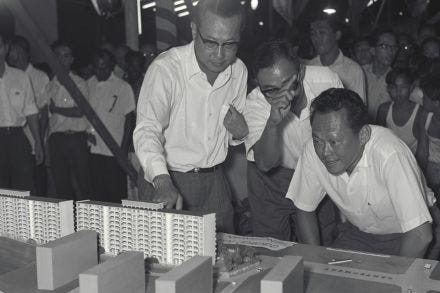

But who would be responsible for this massive housing project bringing all these grand plans to life? That task would fall to Singapore's Housing and Development Board (HDB). And who are the HDB?

As mentioned, after WW2, Singapore experienced rapid population growth, with the population nearly doubling from 940,000 in 1947 to 1.7 million in 1957. And in the Kampongs, living conditions there were less than ideal. The current organisation responsible for public housing in Singapore, was the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT). SIT was trying to achieve the same goals of moving kampong residents to better public housing but faced many problems. Rents for flats were too low to be financially sustainable for SIT yet were also unaffordable for many of the poorer people in Singapore.

So HDB was founded in 1960 to take over the Singapore Improvement Trust's mess of public housing responsibilities. But HDB was off to a slow start. By April 1961, just before the Bukit Ho Swee fire in May, they had only built 2,112 units of housing in the 14 months since inception. But things were about to start moving quickly.

In the aftermath of the fire, HDB focused on the construction of emergency housing and the resettlement of kampong residents into public housing. And with over 3 housing units completed per day at Bukit Ho Swee, the speed of construction demonstrated that the PAP and HDB were able to deliver on their housing promises.

This success by the PAP and the public support gained paved the way for future legislation changes, with the Land Acquisition Act in 1966 giving the government the power of compulsory land acquisition for public development, paving the way for HDBs to flourish.

By 1966, there were 12,562 flats in Bukit Ho Swee Estate, capable of housing an estimated 75,000 people. Five times the number of people who had previously lived in the kampong.

As a result of the Bukit Ho Swee fire and the political capital it gained from the event, HDB estates steadily replaced kampongs in Singapore throughout the 1960s. Over 12,000 families were moved from their homes in the HDB’s first five-year plan, of which three-quarters moved to planned resettlement areas or accepted HDB flats. By 1965, there were over 50,000 units of public housing flats, accommodating 23 per cent of the population. And this growth of public housing in Singapore never really slowed down. Today, HDBs are home to 80% of Singapore's resident population, of which about 90% own their home.

Conclusion

The Bukit Ho Swee Fire is a pivotal yet under-recognized part of Singapore’s history. It allowed the government to act on their disapproval of unauthorised housing, clear kampongs and integrate the population into the social fabric of the state with high modernist public housing.

Were the PAP’s actions of clearing lower-class citizens from their kampongs a continuum of colonial policy? Or were they just trying to help propel Singapore forward? It could be a combination of both. I’ll let you decide.

Want to get in contact? Reply to this email, comment on Substack, or send a letter via carrier pigeon and trust that fate will deliver it.