How AirAsia Conquered Aviation in ASEAN

From 1 ringgit to over $2 billion

Aviation is for the common man. My goal is to enable everyone to fly. It shouldn’t be only for the rich.

- Tony Fernandes

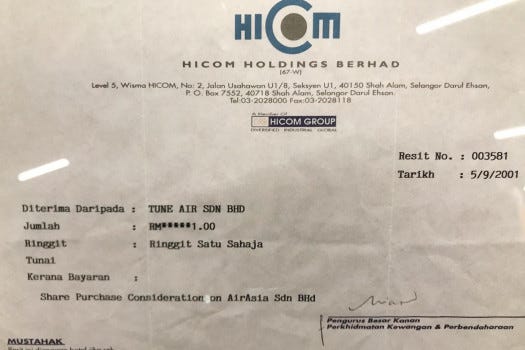

On the 8th of September 2001, Tony Fernandes and Kamarudin Meranun signed an agreement to purchase an obscure airline called AirAsia for the grand total of one ringgit (~$0.26 USD at the time), with 40 million ringgit worth of debts.

Three days later, 9/11 would happen, putting the aviation industry in a tailspin. The price of oil was skyrocketing and passenger confidence was shaken. But AirAsia not only survived this turmoil but would use it as a launching pad to become the largest low-cost airline in Asia and the fourth largest airline overall in Asia.

This is the story of AirAsia.

First-ever sponsor! This issue of Allocators Asia is brought to you by MoneyBits.

MoneyBits is the crypto newsletter for investors and curious people like me trying to stay in the loop.

Every Friday, Dan (the founder) sends a newsletter on the fundamentals of the sector. Forget about bored apes and dog coins, MoneyBits keeps me focused on the important news, and skeptical of the hype.

Join 5,000 other investors and get an insider's view on digital assets. It’s trusted by top fund managers, VCs and wealth advisors too.

Oh, and best of all? It’s free!

Wanna watch this post instead?

Tony Fernandes, then just a boy at boarding school in London, remembers the day his mother passed away as one of the darkest of his life. And still, to this day, he cannot wrap his mind around the fact that he was not able to be with her before she passed, due to the exorbitant price of air travel at the time. He vowed back then that one day he would make flying affordable.

I’ll leave the Tony Fernandes biography video for another day, but the speedrun version of his background is: born in Kuala Lumpur to a mother from Melacca who sold Tupperware (good enough to sell sand at the beach apparently). Tony’s father was from Goa and was an engineer before switching to become an architect, before finally settling as a doctor working for the WHO, in charge of the programme to eradicate malaria and dengue fever.

Tony went to boarding school in England, studied accounting at university (and hated it, one small sliver we have in common) in London, entered the workforce and eventually at the age of twenty-eight took over as CEO of Warner Malaysia. Tony left Warner in early 2001 because the industry refused to innovate but also because he was starting to lose interest, and this is where the story of AirAsia begins.

The Idea for AirAsia

One afternoon in February 2001, Tony was at the Spaniards Inn in London when he saw Stelios Haji-Ioannou, the founder of EasyJet, being interviewed on TV. Tony was intrigued, as he remembers that at the time there were no low-cost airlines that he knew of operating in Asia.

Out of curiosity and excitement, he raced to Luton airport and was blown away. It felt like the entire airport was easyJet branded – orange was everywhere. Passengers were flying off to Barcelona for £8 and Paris for £6. From the blanket branding of the airport to the simplicity of their product offering, it was a sight to behold. At that moment, Tony Fernandes decided he was going to start an airline.

But how do you start a business if you know nothing about the industry? The answer was to do something Tony excelled at: talking to people.

He spoke with Sir Brian Walpole, one of BA’s most well-known pilots and had been the Queen’s Concorde pilot; Clive Beddoe, one of the founding shareholders of a low-cost carrier called WestJet based in Canada; and his old mate, Mark Western, who was a lawyer involved in aircraft leasing, who then suggested he speak to GECAS (GE Capital Aviation Services) – the aviation leasing arm of GE and one of the biggest in the industry at that time, with a fleet of nearly 2,000 planes leased out to airlines in seventy-six countries.

But before anything else, they needed an airline licence. And getting one required political connections, for which they had none. So they approached Pahamin Ab Rajab, who was the secretary-general of the ministry at the time and previously in the Ministry of Transport, to be their chairman for this still unnamed airline venture. Pahamin managed to arrange a meeting with Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad in July 2001, their only chance to get this airline off the ground.

Mahathir was receptive to the idea of a new low-cost airline, but with a caveat:

“you’ve got to buy an airline. I won’t give you a licence to create a new one because I’ve had too many failed airlines.”

Which basically meant:

The search for an airline began. They approached an airline called Pelangi Air but they came back with, “Give us $40 million and we’ll turn the airline round for you.” Tony remembers “We looked at the books and it was a joke – only God could have turned that company around. We politely declined.” [Note: Pelangi Air ceased operations in 2001, not even god could save it apparently]

Fast forward a few weeks, and with no further progress on the airline shopping, Tony was playing golf and saw the corporate communications director of DRBHICOM – one of Malaysia’s leading manufacturers. Tony knew they owned a tiny airline called AirAsia but knew nothing else about the airline.

Because AirAsia at that time was so insignificant that, even as desperate as they were, it hadn’t appeared on their list of potential airlines to buy. Still, Tony went up to him and the conversation was brief but went like this:

‘Hey, I hear you have an airline.’

‘Yeah, Wanna buy it?’

‘Yes,’

‘You can have it tomorrow, we don’t need it.’

So Tony went home that night and frantically tried to learn more about AirAsia.

And what did AirAsia look like? A few domestic routes, a couple 737-300s and about 200 staff. It had been set up in the mid-nineties by Tan Sri Yahaya Ahmad, the founder of DRB-HICOM, with the aim of becoming the second-largest carrier in Malaysia after Malaysian Airlines.

Tragically, Ahmad died in 1997 in a helicopter crash and AirAsia had been nothing but a burden on DRB’s books ever since. By 2001 it had amassed 40 million ringgit in debt. Tony and Din went to see the deputy CEO of DRB the next day, who was keen to rid his company of the airline:

‘You can have the airline tomorrow. How much do you want to pay for it?’

‘One ringgit?’ Tony said, half taking the piss

‘You can have the airline for one ringgit provided you remove our corporate guarantee from GECAS’

Let’s break that down. Firstly, remember that GECAS is GE Capital Aviation Services – the aviation leasing arm of GE. And a corporate guarantee is an instrument that is provided by a parent company when one of its smaller subsidiaries enters into a long-term agreement with a third party. So in this case, DRB-HICOM guaranteed payment of the leases for the aircraft for as long as the lease was in place. But obviously, DRB-HICOM wanted to sell the company but didn’t want to continue to provide the guarantee.

So, Tony and Din needed to get GECAS’s approval for the acquisition because they needed the guarantee that the leases for the two planes that AirAsia operated would be paid. GECAS had entered into the leases for the planes because DRB-HICOM owned the airline. Would they be sympathetic to the young industry upstarts and their business plan?

Fortunately, they were able to remove that guarantee, so they could go ahead and buy AirAsia for MYR 1.

The deal was signed on 9 September 2001, subject to due diligence… only 2 days later 9/11 happened, the aftermath turning the aviation industry on its head.

After the initial shock of 9/11 subsided, Din rang Tony and asked: ‘Should we still do this?’

And he was justified for asking: The short-term economics were horrible in every conceivable way: the price of oil was going through the roof and passenger confidence was absolutely plummeting. To most people, starting an airline at this moment in history seemed like the stupidest idea ever. But Tony knew they had to do it. “we’ve got to make sure people can fly.”

Just four days after 9/11, there was some positive news for AirAsia. Originally, they were planning to swap their two existing 737-300s for the smaller and older 737-200 model because the 300s were too expensive to run. But GECAS approached AirAsia with a proposal. Because the lease rates collapsed because of 9/11. They offered AirAsia to keep the 737-300s but they would halve the rate. This change benefited them big time: projected revenues went up because the 300s carried about twenty extra seats, and the costs were reduced because the 300s were more efficient and powerful, meaning fuel costs and flight times were reduced.

What did AirAsia have?

A licence

Two aeroplanes (registrations 9M-AAA and 9M-AAB)

Staff

And they had even inherited some routes.

What didn’t AirAsia have?

Money

Din and Tony were trying to remortgage their houses to have something to put in as they forecasted that they’d need MYR 20 million to get the business running

In the end, they agreed that they’d just have to run it on the cash they took in. If they wanted to operate a low-cost airline we’d have to practise what they preached and survive hand to mouth.

Early Days and ramping up

Finally, on the 8th of December 2001, once the due diligence had been completed, Tony and the board finally signed for and took over the airline.

But they couldn’t implement their low-cost model immediately because remnants of the old airline remained. They relied on existing routes and structures for the first few weeks until they could convert the planes and introduce the full low-cost plan. The low-cost model was to:

Frequent short or mid-haul flights so they can operate a larger volume of flights per day, optimally utilizing their fleets and increasing passenger traffic.

Point-to-point transit model - Low-cost carriers fly from point A to point B with no connecting stops in-between. Unlike the traditional hub-and-spoke model, where two or more cities are connected via a hub airport, point-to-point allows Low-cost carriers to have shorter travel times and connect cities directly with a lower dependence on airports.

Operations at smaller or cheaper airports - These so-called secondary airports are less congested and offer more available slots and faster taxiing times. This not only helps LCCs to maintain their large volume of flights but also increases their negotiating powers with the airport.

Single service class, no business seats.

Unbundled ancillaries - Selling cheap tickets doesn’t generate much revenue for the carriers, and these base fare earnings are heavily taxed. To generate more revenue, LCCs charge an extra fee for any additional service.

Direct sales - Skip the middleman (and the fees associated) like with travel agents and partners

Some people joke that we’re just lucky that low-cost airlines don’t charge us for emotional baggage too.

But over the course of the next six months, AirAsia converted the planes to increase the number of seats in the cabin from 124 to 148 by ripping out business class completely. Once converted, their fares were aggressively low. The normal fare to Kota Kinabalu was MYR 400, but they were offering seats at MYR 149.99. Through 2002, AirAsia added three more planes and within seven months they had wiped out our portion of the MYR 40 million debt.

In the early days, even something as simple as adding flight destinations was tougher than woodpecker lips. It took them seven years to be able to fly direct to Singapore. So Tony decided on a workaround where they’d fly to Johor in southern Malaysia – about a forty-minute bus ride from Singapore – and take their passengers over the border by bus. They launched the route and on the very first day, once the passengers reached the Singapore border, the bus was impounded and the passengers dumped. They couldn’t get them in – that was the level of opposition they faced initially.

However, AirAsia would eventually hit some heavy financial turbulence. In 2008 when the financial crisis hit Wall Street and global markets, AirAsia was badly exposed by hedged investments they’d made on the oil price. Prior to the financial crash, the price of oil was going through the roof and killing the airlines' bottom line, so AirAsia took hedged positions to try to control our exposure. When the global crisis hit, the price plummeted, and it wiped out all their cash – around MYR 1 billion. They were down to MYR 5–10 million, which wasn’t far off where we started in 2001. A renewed intense focus on cost, aggressive marketing and the discipline to get back to their frugal early-days behaviour meant that within two years we were back to having 1 billion ringgit in cash. But the lesson was learned, avoid the derivatives game and if hedging, it is only for a year and fix all interest rates and exchange rates where possible.

But by 2012, AirAsia was a real force in ASEAN aviation: a fleet of 118 planes and had carried nearly 200 million passengers since exception. Their pace of growth left a lot of competitors in their wake and the more established airlines were starting to worry.

And because of this, an opportunity arose. In 2012, the CEO of Malaysia Airlines, Idris Jala, had been to see Nazir Razak, Chairman of CIMB Group, which is one of the largest financial services providers in Malaysia and ASEAN, and suggested that the Malaysia Airlines and AirAsia explore the possibility of a merger. Malaysia Airlines was struggling at the time and had been for a number of years. They had also been asking the Prime Minister for a refinancing package to secure the airline’s future.

But Tony was excited about the possibility of a merger - it was a sign of how far they had come that the national carrier wanted to join forces with them. On paper, the merger with AirAsia deal made sense. Blending Malaysia Airlines’s fleet, destinations and economies of scale with AirAsia’s innovation and execution.

But the political pressure groups and unions were strongly against the proposed merger. And in the end, Mahathir said that the deal was economically sound but a political minefield. So the government decided to shelve the potential merger.

For AirAsia, it was an opportunity that didn’t quite work out. But for Malaysia Airlines, the fallout was more than that. After the deal fell apart, they had to go through a massive restructuring which led to thousands of job losses. It was frustrating but, as far as AirAsia was concerned, still a milestone: the national full-service carrier would have merged with us if the political climate had been right. But the key takeaway was that AirAsia was on the right track

AirAsia has basically gone from strength to strength. As of December 2019, AirAsia had 275 aircraft, across 8 airlines. Flew to 159 destinations across 23 Markets. Had flown 100 million passengers annually and over 600 million total passengers and conducted over 11,000 flights per week.

Tony in his autobiography said that after sixteen years, his business philosophy can be summed up in 3 points.

A company must be able to adapt to change.

A company must be disruptive – it must create models that weren’t there before. And,

A company must have the right people.

But what about the future of AirAsia? From Tony’s 2017 autobiography:

The future is now about moving AirAsia from ‘just’ an airline to a big data technology company, because that’s what I see as the next frontier. Data is the new oil and I want AirAsia not only to be the world’s best low cost airline every year in the future, I want it to be a data platform to drive other businesses.

Let's not beat around the bush, Covid has been a spanner in the works for AirAsia. But the same can be said for all passenger airlines. AirAsia is the largest low-cost airline in Asia and the fourth largest airline overall in Asia. Not bad for a company worth 1 ringgit just 20 odd years ago.

You can find previous posts here. I also interview legends at Compounding Curiosity and lurk on Twitter @scarrottkalani.

Want to get in contact? Reply to this email, comment on Substack, or send a letter via carrier pigeon and trust that fate will deliver it.

Good

Great article